How to Improve Your GMAT Verbal Score

Every GMAT teacher or tutor has heard these words, particularly from native English speakers: “I feel fine about the verbal; I just need to focus on quant.” Since even those with quant-heavy jobs don’t regularly use the rules and formulas used on the GMAT, many people approach this test with a feeling that they need a lot of time to dust off all that math they haven’t seen in years but will just pick up the verbal.

But for every twenty people who “really need to focus on quant,” I estimate that only one is correct. Maybe.

Consider a daunting truth: if you’re going for a 700 or higher, you’ll likely need at least a 38 in verbal (40, if you’re aiming for a 720+). These are really high verbal scores.

Consider another daunting truth: for Reading Comp (RC) and Critical Reasoning (CR) – two-thirds of the verbal section – there are no rules to memorize at all. There are just words on a page, and your thoughts about them. There are patterns to pick up, and certain logical games that are repeated, but, aside from some grammar rules in Sentence Correction (SC), it’s stuff you already know (and you probably know most of the SC rules as well). So how do you improve on questions for which there’s ‘nothing’ to learn?

Well, first, it’s important to always remember that the GMAT is not really testing rules. I can show you a challenging geometry problem that only requires you to know the formula for area of a rectangle (a rule you probably remember), a difficult sentence correction question with a very effective trap regarding simple subject-verb agreement (a rule you use effortlessly all the time), and a tricky critical reasoning passage that merely requires you to catch the difference between "allergic reactions to any substance" and "allergic reactions to a specific substance" (a distinction that’s probably obvious with a few seconds thought).

4 ways to improve your GMAT Verbal score

So, let’s talk about how to improve your GMAT Verbal score beyond the rules by using a process that will, by the way, also help you to maximize your Quant and Integrated Reasoning scores.

Change the way you read and process language (make it structural)

One of Stacey’s biggest pieces of advice for improving on the whole GMAT was: “Focus on Reading Comprehension for the whole GMAT.” I echo that advice. But you’ve been reading for almost all your life! How can you improve comprehension?

A lot of students complain about how weird certain sentences on the GMAT are written. True, sometimes the difficulty is intentionally obfuscating. However, as language is a tool to transmit either emotion or thought and the GMAT ain’t worried much about emotion (leave that for novels and poems), the language on this test is used to convey thoughts that need to be exact, specific, and unambiguous in order to ensure a question has only one objective right answer. Getting such logical precision in a sentence can actually be incredibly difficult (and frustrating). Inevitably, complicated-but-specific meaning requires a very thoughtfully constructed sentence, and interpreting it a thoughtful deconstruction of it.

This isn’t just for SC. It turns out that accurately assessing the specific meaning in written text is an enormous part of the entire GMAT. Details, qualifiers, quantifiers, subsets vs. totals, accurate comparisons – all these little ideas that language can transmit – can get lost in a sea of words.

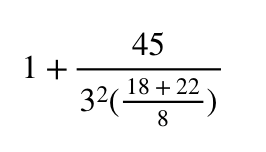

Surprise math break: what is the value of the expression below?

You might read that left to right, top to bottom, but I bet that’s not how you solve it. There are a few options, but you probably start in the middle, by adding the 18 and 22, or perhaps by seeing ‘3^2’ is 9 and 45 over 9 simplifies to ‘5.’ Regardless, you thoughtfully and strategically interpret the information in a different order than the one presented.

You can (and should) start doing something similar with language. A math expression like the one above is a combination of different nested relationships between numbers; a sentence is the same thing with words (and, by the way, a paragraph the same thing with sentences). Just as the ‘final value’ of the expression is determined when all the relationships are accounted for, so too is the ‘final meaning’ of a sentence (as is the main point of a paragraph). In either, you aren’t obligated to deal with the ‘pieces’ in the order they come.

Consider these two sentences:

- A man with his dog, his child, and a marching band walks by.

- A man with his dog, his child, and a marching band walk by.

Neither is strictly wrong – and almost every word in the sentence is identical, in the exact same order. Yet, by removing that little ‘s’ at the end of the verb, the structure of the sentence – and hence its meaning – changes. Can you see how?

In the first, the verb is singular, so the only option is the ‘man’ walks by. The other things – the dog, child, and marching band – are things the man is with. They are part of a modifier describing the man. In the second, the verb is plural, so the man, the child, and the marching band all walk by (‘with his dog’ is now the only modifier of the man). Start your interpretation of this sentence from that verb, and then piece together the subject from there. That will tell you what roles the 'child' and 'marching band' play, giving you, at last, the full meaning of the sentence.

(“But which is right?!” I hear you ask. That’s not really the point right now, but it does seem strange to say the man is with a marching band. Is it his marching band, like the dog and child are? That seems unlikely, so I’m inclined to say the second. Check number 910 in the Official Guide 2022. It was the inspiration for this example.)

You want to become an absolute bloodhound for sentence deconstruction. This doesn’t require a deep knowledge of the minutiae in the rules of grammar. It just requires you to develop the ability to specify what roles the different words (or chunks of words) are playing in a sentence. In order to do that, maybe you don’t read every word, top to bottom left to right. You find the connections in the sentence and consider those first (and when reading a paragraph? Same idea!).

Start a list of common structure keywords. ‘Which,’ for example, is a word that indicates what comes after it will describe the noun before it. Conjunctions such as ‘and,’ ‘but,’ ‘although,’ and ‘because;’ transitions such as ‘however’ or ‘therefore;’ comparisons such as ‘like,’ ‘unlike, ‘more,’ ‘less,’ and words that end in ‘er’ or ‘est;’ parallelism openers such as ‘both,’ ‘either,’ and ‘neither;’ prepositions such as ‘of,’ ‘in,’ ‘for,’ and ‘with’ – all of these have major structural and logical power, and should pique your GMAT antennae any time you see them.

Developing a sense for Subject-Verb Agreement, Conjunctions, Modifiers will change everything about your GMAT experience. (I know that sounds a little dramatic, but that has been my experience in the 10 years I’ve been teaching the GMAT.)

And hey, while we’re thinking about a similarity between sentence structure and solving a math problem…

Treat the whole verbal section more like math

When I first spoke with Stacey about this article, she said something that we had always sensed but never verbalized in this exact way: “In Verbal, the inferences you make should feel as objective as the inferences you make in quant.”

What does that mean? Well, consider a triangle with two 70 degree angles. You’d infer that the third is 40, because that’s just the objective rule – the angles of a triangle add to 180. Similarly, if ‘Garfunkles are better suited for bulteration than are thrillpoppers, as thrillpoppers tend to hercoptolate at the necessary astral-plane for bulteration,’ then it’s just objectively the case that ‘Garfunkles are less likely to hercoptolate when they bulterate than are thrillpoppers’ (you’re not going crazy, those weird words are gibberish – but the logic isn’t).

That fact is not written, but it must be true based on the logic expressed in that language:

- T’s tend to H when at the necessary A to do B.

- That fact makes T’s worse at doing B than G’s are.

- Therefore, when G’s do B, they don’t H as often as T’s do.

(Notice when laying out the logic, I didn’t express the ideas in the same order or with the exact same words as what was written – just as with parts of a sentence, you need not untangle logical ideas in the same order they are presented, either! Notice also what I don’t infer: that ‘G’s don’t H,’ that ‘T’s can’t B,’ that ‘most B is done by G’s’ (what if there are just way, way more T’s out there?)).

A student I was recently working on CR with said, “It’s like math with words.” It was the kind of realization that gives me the goosebumps of satisfaction in helping a student get it.

Use that mindset for your verbal prep. Make it feel like ‘math with words.’

To that end…

Deeply analyze questions and answers (and the thoughts you had about them)

Since the verbal section amounts to ‘words on a page and your thoughts about them,’ how you review will be a huge determinant of how much you improve.

Most students do a decent job of specifying why a right answer is right and why a wrong answer is wrong (though most could probably do even more with the latter!). But very few students ask the questions that will really drive improvement: “Why was I tempted to choose the wrong answer? To not choose the right answer?” Sure, you might have resisted both temptations and chosen the right answer, but still ask yourself these questions in your review.

Again, try to treat it more like math. Somewhere in the tempting wrong answers, the ‘math’ doesn’t check out. There’s some detail or some subtle twist that doesn’t support choosing that answer. For the right answer, there’s a solid, concrete, text-and-logic based reason why that ‘math’ checks out – but it can be tricky to spot. How did the GMAT hide the ball?

I often get asked about a verbal question, “Aren’t both of these right? Is it just that this one is more right?” But the cold, hard truth is that the right answer to a verbal question is as objectively right as the right answer to a quant question, and the wrong answer as objectively wrong (and, by the way, GMAC does extensive statistical research on questions to ensure that a question is fair and has one objective right answer).

So review questions – and the way you thought about them – deeply and carefully, and identify the correct line of reasoning to justify the right answer and to eliminate wrong ones. And while you’re doing that…

In general, cultivate a curious mindset

- T’s tend to H when at the necessary A to do B.

- That fact makes T’s worse at doing B than G’s are.

- Therefore, when G’s do B, they don’t H as often as T’s do.

This is another piece of advice that’s important for the whole test. Asking yourself “Why?” “How?” and “What could?” often – and trying to find an answer with straight-forward reasoning or by something in the text itself – is a major skill. Why does the author think [x]? How would [x] be true? What else could be true?

Most Reading Comp Passages end up being passages about a ‘why’ and/or a ‘how.’ Identifying that is a huge first step to comprehension. “Why were the early feminists on the royalist’s side?” “How did Native American reservations get water rights even if such rights weren’t explicitly mentioned in treaties?” “How did the mammalian skeleton first evolve – for hunting or protection?” are all questions that official RC passages deal with at a macro level. It’s amazing how often asking yourself the right question will help you find the answer to the one that is explicitly asked on the test.

Conclusion

I hope this article has opened your eyes to the importance – and possibility – of improving your verbal skills. There are plenty of resources to help you along the way. Download Manhattan Prep’s Foundations of Verbal book completely free, and sign up for the official GMAT starter kit at mba.com to get free practice questions and two full practice tests.

Developing a consistent structure-based approach to meaning, treating verbal more like the math, cultivating a habit for thoughtful question/answer review, and ramping up your curiosity are all skills that will raise not just your verbal score, but your skills on the whole GMAT.

FAQ

Why is my GMAT verbal score not improving?

For Reading Comp (RC) and Critical Reasoning (CR) – two-thirds of the verbal section – there are no ‘rules’ to memorize at all. So how do you improve on questions for which there’s ‘nothing’ to learn?

How can I improve my GMAT Verbal in 2 weeks?

Asking yourself “Why?” “How?” and “What could?” often – and trying to find an answer with straight-forward reasoning or by something in the text itself – is a major skill. Why does the author think [x]? How would [x] be true? What else could be true?

Developing a consistent structure-based approach to meaning, treating verbal more like the math, cultivating a habit for thoughtful question/answer review, and ramping up your curiosity are all skills that will raise not just your verbal score, but your skills on the whole GMAT.

How can I improve my GMAT Verbal score to 40?

Change the way you read and process language by making it structural. Develop a sense for Subject-Verb Agreement, Conjunctions, Modifiers. Treat the whole verbal section more like math and review questions – and the way you thought about them – deeply and carefully, and identify the correct line of reasoning to justify the right answer and to eliminate wrong ones.

Download Manhattan Prep’s Download Manhattan Prep’s Foundations of Verbal book completely free, and sign up for the official GMAT starter kit at mba.com to get free practice questions and two full practice tests.

Is a 40 GMAT Verbal score good?

If you’re going for a 700 or higher on the GMAT exam, you’ll likely need at least a 38 in your verbal score and a 40, if you’re aiming for a 720+ score. 38 and 40 are both really high verbal scores.